Violets, spicebush, and ferns form a scruffy understory below the canopy of white pines. Nearby, bright yellow goldenrods and purple coneflowers beckon local bees and butterflies. During the day, this landscape is a playground for blue jays, cardinals, and robins. Under the cover of night, raccoons come here to raise their young, and hordes of fireflies stream a light show on prairie grasses. This isn't some bucolic park or protected national forest: It's Danae Wolfe's half-acre yard in suburban Ohio.

When Wolfe and her family bought the property eight years ago, it looked like most of the others on a block: a perfectly manicured green lawn with a few flower beds here and there. By introducing native species, limiting pesticides and chemical fertilizers, and allowing for more natural growth, Wolfe has become one of an increasing number of homeowners embracing wildlife-friendly gardens. In the year ahead, expect to see more gardeners take a similar walk on the wild side in the name of protecting ecosystems—and our own health.

Meet the experts

Danae Wolfe

Danae Wolfe is a macro photographer and conservation educator. She is the founder of Chasing Bugs, where she strives to promote sustainable home landscape practices that support insects and spiders while fostering an appreciation of the beauty and diversity of bugs around the world.

Susannah B. Lerman, Ph.D.

Susannah B. Lerman, Ph.D., is a research ecologist at the USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station. She investigates how native birds, bees, and other wildlife respond to different urban green space management.

Doug Tallamy, Ph.D.

Doug Tallamy, Ph.D., is a professor of agriculture and natural resources at the University of Delaware, where he has authored 100+ research publications and has taught insect-related courses for 41 years. He is also the founder of Homegrown National Park.

Allison Messner

Allison Messner is the CEO of Yardzen—an online landscaping design platform that prioritizes sustainability.

Jean Ponzi

Jean Ponzi has been a strong environmental education resource for the St. Louis region for nearly 30 years. As green resources manager for the EarthWays Center of Missouri Botanical Garden, she currently promotes the integration of sustainable thinking, planning, and action into business practices as co-manager of the St. Louis Green Business Challenge.

Why grass isn't always greener

Drive through the suburbs of the U.S., and one thing will become very clear: Americans are obsessed with grass lawns. This wasn't always the case. Back in the 1700s, grass lawns were a status symbol, and only the rich could afford to keep their land so neat. The widespread introduction of the lawn mower around 1900 made it so everybody could manage their own lawns, and green grass went from a luxury to a necessity (at least, if you want your neighbors to like you).

These days, Americans maintain around 44 million acres of residential lawns sprawling over 30% of the land area in the continental U.S. Grass has become the largest crop in America, and it's a high-maintenance one—often requiring a hefty amount of water and fertilizers to keep it in the pristine condition homeowners associations now expect. But while they have become a symbol of being a good neighbor, grass lawns are "ecological dead zones" that do almost nothing to support nonhuman residents.

Compared to other plants, perfectly manicured grass lawns do not absorb carbon from the atmosphere1 or support much wildlife biodiversity. Susannah B. Lerman, Ph.D., a research ecologist at the U.S. Forest Service, explains that the spread of lifeless grass lawns is disrupting local food webs—which could have catastrophic consequences on planetary health.

Doug Tallamy, Ph.D., an ecology professor at the University of Delaware and co-founder of Homegrown National Park, explains that protecting wildlife in national parks and conservation zones but forgetting about our own backyards will ultimately lead to our downfall. "We need to put life back into our public spaces and private spaces as fast as possible," says Tallamy, "because that's what keeps us alive on this planet."

Taking a walk on the wild side

We'll never get rid of grass lawns entirely, but how can we make them less harmful? That's the question more green thumbs are increasingly grappling with. A 2022 National Gardening Survey found that more respondents are now open to transforming a portion of their lawn into a wildlife-friendly native landscape, as Wolfe did in Ohio.

Native landscaping tends to be better for the surrounding environment than nonnative plants for a few reasons. "[One] potential issue is that some nonnative plants can become invasive to an area. They may look beautiful and thrive in a nonnative landscape, but invasive plants are hyper-competitive and don't have the same animals or weather conditions to keep them in check in this new environment. Invasive species can spread rapidly and ultimately outcompete native vegetation, leading to a loss of biodiversity and ecosystem disruption," explains Allison Messner, CEO and co-founder of Yardzen, an online landscape design company.

Messner adds that nonnative plants have their own root systems and growth patterns, potentially leading to issues with soil stability and erosion control—another reason to switch over to native species.

Tallamy has seen this shift play out over the course of his career. When he wrote his first book, Bringing Nature Home, back in 2007, the native plant movement was in its infancy and very niche. Now, he estimates that he gets about three to four requests to give talks on biodiverse gardening every day.

"There are all kinds of conservation groups around the country that are building ecological integrity on our private properties. That just wasn't happening before," he says. One such group is Pollinator Pathway, a nonprofit that helps people establish pollinator-friendly habitats in their communities. Since its founding in 2017, the group has supported projects in 300 towns across 11 states.

Creative campaigns have also popped up to help people take on specific actions in their yards. The #LeaveTheLeaves campaign—especially relevant during this time of year—encourages leaving fallen leaves on one's property during winter to allow critters like bumblebees, ladybugs, and caterpillars to burrow homes in the decay. #NoMowMay is an invitation to let one's lawn grow for an entire month during spring to give pollinators access to more early season wildflowers. To educate curious neighbors, people can now print out lawn signs like this one that reads: Lazy Lawn Mower Alert: We're mowing less to improve pollinator habitat and contains a QR code that passers-by can scan for more information on how to get involved.

Nowadays, entire communities are banding together to take on such pledges. Jean Ponzi, an environmental educator in Missouri and green resources manager for the EarthWays Center of Missouri Botanical Garden, notes that the community of Webster Groves, Missouri, took the no-mow pledge this past spring. They were sent 300 signs but could have used more, says Ponzi. In the St. Louis region, a hot spot for native wildlife plantings, they now also have a series of regular virtual talks on native landscaping through the St. Louis County Library that are attended by over 6,000 people on average.

Clearly, interest in creating wildlife-friendly gardens is growing. But for this moment to become a full-blown movement, we'll have to make it more accessible. As it stands now, many people don't have the time or money to make these changes, or they don't own their own property in the first place.

New financial incentives in certain parts of the country could help change this. In California, for example, homeowners can receive a $3 rebate for every square foot of lawn they remove and replace with more drought-tolerant landscaping. In the last year, Los Angeles bumped that up to $5 per square foot (up to $15,000) in an effort to conserve the city's dwindling water supply. These programs don't just exist in the water-starved west: Minnesota also has several cost-share programs focused on growing prairie and native grasslands, while Missouri offers grants for using plants to manage stormwater runoff.

A handful of states, such as Florida, have also passed laws forbidding homeowner associations from forcing residents to adhere to unsustainable landscaping practices. Wolfe, who is also a conservation educator and author, notes that these changes are long overdue. "It is so ridiculous to tell people that they can't support nature in their landscape—and instead, they need to manage a monoculture of carbon-intensive turf grass," she says. "We need societal change—and I think we're starting to see it."

Why gardening this way will pay off for our health

As more people let their yards go a little wild, local critters aren't the only ones who will benefit. We'll see a boost in our own well-being too.

Research repeatedly shows that tuning into elements of nature—like the patterns of tree leaves and the songs of birds2—can help reduce our stress and anxiety, lower our blood pressure, and boost our overall mood. The more access we have to these features, the better for our mental and physical health. Not to mention, we avoid some headaches (and noise pollution) when we don't constantly need to mow our lawns and blow away our leaves.

Protecting the green spaces in our own backyards can also help us get to know our neighbors. After all, while one wildflower-rich garden is great for pollinators, an entire strip of them will be even more enticing, so this work presents an opportunity to band together for a common cause. In doing so, community members can combat the very real health threats of loneliness and isolation.

And who knows: Once you get started greening up your yard, you may be inspired to take on other environmental actions that are personal and purposeful. "In a world that can feel very heavy, to be able to look at the small part that I'm playing has been so empowering to me," Wolfe says of her yard transformation.

Experts note that you don't need an expansive garden or acres of land to make a home for your local wildlife. You also don't need to dedicate lots of time or money to the pursuit. Small changes with sizable impacts include turning off your outdoor lights at night so you don't throw off birds and insects, limiting unnecessary pesticide use, letting leaves decompose into a natural fertilizer, and mowing your lawn every two to three weeks instead of one.

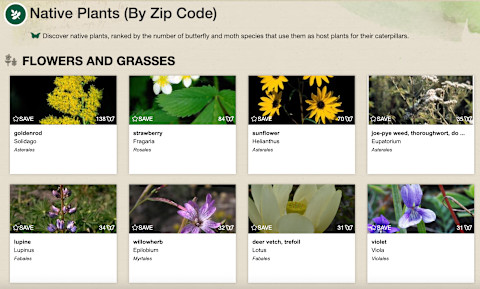

For those in regions that get plenty of rain, Tallamy notes that one of the simplest ways to make a difference is to plant trees in your yard. In the area underneath it, plant native plants that can attract birds, sequester carbon, and support a healthy watershed. This will also help naturally trim down your lawn area, but you can also set aside some "no-mow" or "no-go" areas on your property if you have the space. As for where to find plants native to your area, the Pollinator Partnership Ecoregional Planting Guides and National Wildlife Federation Native Plant Finder are great places to start.

"It's about starting small," says Wolfe. "One patch at a time, just build. You'll start to see the benefits of that pretty quickly when the wildlife starts to return."

After nearly a decade of removing invasive species, planting native landscaping, and creating habitat for the locals, Wolfe saw something new this year: Thanks to a well-positioned bird camera, she got to watch blue jays, cardinals, and robins taking to her yard to teach their young how to find food. She marvels: "The fact that these animals feel like our landscape is a good enough space to bring their offspring and teach them how to forage—what could be a better sign that we're on the right track than that?"

Forecasting the future

In 2024, you start to notice some changes during your daily walk through the neighborhood. In autumn, the season's vibrant leaves are left out to feed lawn critters instead of sitting on the curb for townwide collection. Come spring, textured clover and colorful wildflowers take the place of row upon monotonous row of grass lawns. Throughout the year, yard signs aren't just for politicians anymore; they're there to express a gardener's commitment to creating space where humans and nature can coexist.

In an age when disconnection from the natural world drives so many issues, interacting with the nonhuman world is a balm. And Wolfe and other wildlife-friendly gardeners are proof: There's no better place to do it than your own backyard.